An Integrated Analysis of Oral Health in Canada

- ALeeRDH

- Jul 19, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 1, 2019

Throughout my participation in MHST 601 – Critical Foundations in Health Disciplines, in the Master of Health Studies graduate program at Athabasca University, I have advanced my knowledge regarding components that influence and the impact health of Canadians. I have been challenged to look at health from various perspectives, strengthen my research and analysis skills, and develop a comprehensive collection of curated content that aligns with my professional interests. I have been able to clarify and enrich my understanding of a professional interest of mine – promoting oral health.

As I progressed through the MHST 601 course, the topic of oral health promotion and education, specifically for children’s oral health, became the main themes of my blog posts and content curation. Oral health practices are necessary at all stages of life; from parents/guardians providing an oral sweep after an infant’s bottle of milk, to cleansing a denture. Fostering positive oral health practices at every stage of life is imperative. As I reflect on my growth throughout MHST 601, I will provide an integrated analysis of children’s oral health care in Canada with a focus on my home province, Nova Scotia.

Inter-professional Connectedness

In the first week of the course, I performed a self audit and created blog posts about my social media use, professionalism, and curation of health information and then developed a corresponding plan of action. During my Diploma in Dental Hygiene (DipDH) at Dalhousie University, I took a communications course that helped me learn about my presence in social media. As an educator and practicing registered dental hygienist (RDH), I am a role model for future oral health professionals and strive to create a positive professional identity and express this appropriately through social media. This lead me to create professional accounts dedicated solely to dental hygiene and health information dissemination.

To better facilitate sharing health information, proper content curation is necessary. My previous method of content curation was inadequate. To improve, I sought out alternative options including OneNote, Pocket and PearlTrees. Each option had strengths and weaknesses, but I ultimately chose to use PearlTrees as my primary content curation source. As my collection of health information grew, I built my ePortfolio, linking my content curation and professional social media presence; I also expanded my social network by joining Twitter to share oral health information and engage in inter-professional connectedness.

Federal and Provincial Health Systems in Canada

Oral health programs vary in each province, but one universal component is provincial funding. In my blog post titled “Registered Dental Hygienists and the Canadian Health Care System” I discussed the Canada Health Act and establishment of publicly funded insured health services fulfilled by the provinces and territories under the Canada Health Transfer. In Nova Scotia, publicly funded dental and dental hygiene treatment for children is provided by the Nova Scotia Children's Oral Health Program from infancy to the month of the child's fifteenth birthday. Coverage is limited to:

one routine dental exam per year

one fluoride application (a second application may be eligible in some cases) per year

two routine x-rays per year

one preventive service – for example, brushing and flossing instruction, and/or cleaning

molar sealants, fillings and necessary extractions

(Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, 2019)

It does not, however, cover additional dental treatment such as orthodontics; this must be paid for by private insurance or out-of-pocket.

RDHs are not recognized as service providers for the Children's Oral Health Program, or any other publicly funded dental programs for that matter. The College of Dental Hygienists of Nova Scotia (CDHNS) created a white paper "Dental Hygienists Prevent More to Treat Less" (2014) that put forth the recommendation to amend the N.S. Health Services Act to include dental hygienists as primary care providers. It also included an impactful statement of the importance of RDHs to oral health and overall health care of Nova Scotians.

“Dental hygienists are critical partners on collaborative inter-professional primary care teams, uniquely qualified to help improve the oral health of Nova Scotians. As preventive therapists, health educators and holistic care providers, dental hygienists are positioned to contribute meaningfully to individual and community oral and overall health in a variety of settings where their practices can be fully matched with primary health care principles of universal access, equity and affordability.” (CDHNS, 2014, p. 18).

Health of Canadians - Understanding Health

The World Health Organization's definition of health "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity" has been the most widely accepted definition since its creation in 1948. Among others, Huber (2011) criticized this definition for being virtually unobtainable as it indicates that a state of well-being must be “complete” or absolute. Bircher (2005) expressed that demands on an individual’s health will change over their lifespan and being able to adapt to these changes is indicative of our state of health. As I searched further into alternative definitions and descriptions of health, I learned that, in my opinion, health should be considered a concept as I do not feel it can be rigidly defined.

Health of individuals and the population at large is shaped by the interrelationships of key factors called determinants of health. These vary across the world, but in Canada, there are eleven key determinants of health:

income and social status

employment and working conditions

education and literacy

childhood experiences

physical environments

social supports and coping skills

healthy behaviours

access to health services

biology and genetic endowment

gender

culture

(Government of Canada, 2019)

My search for information on the determinants of health in Nova Scotia uncovered the Healthy Development Protocol (2014) created by the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. Oral health is influenced by the determinants of health; this protocol describes public health planning, assessing, implementing and evaluating actions with consideration of health inequities and inequalities pertaining to the determinants of health in Nova Scotia in the early development stages of life.

Multilevel Approaches to Understanding Health - Beyond the Individual

At the mid-point in the MHST 601 course I was tasked with applying a multilevel approach to health to a topic of interest in my profession. As the weeks progressed, I had collected various resources on children's oral health and chose to use a socio-ecological model to examine influences on children's oral health. Figure 1 describes the levels of influence on children's oral health that I explored.

I discovered that at each level, a child's oral health condition can be greatly influenced. At the intrapersonal level, ability to perform dental hygiene care, snacking habits and food preferences, as well as a child's knowledge and beliefs about dental treatment influence the risk of a child experiencing dental caries; these are shaped through exposure at the interpersonal level. Education of the child's family or caregivers is imperative to establish good oral health practices early in life. The Canadian Dental Association (n.d.) recommends early introduction to the dental office, typically by the child's first birthday. This provides an opportunity for oral hygiene instruction, nutritional counseling and will help the child learn that dental visits are a regular part of health care. At the community level in Nova Scotia, water fluoridation provides equal access to those of any socio-economic status, yet not all communities are fluoridated (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017; University of Toronto, 2012). For those communities that are not, school-based fluoride mouth rinse programs are provided by public health as an additional opportunity to prevent dental decay (Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, 2004).

Vulnerable Populations

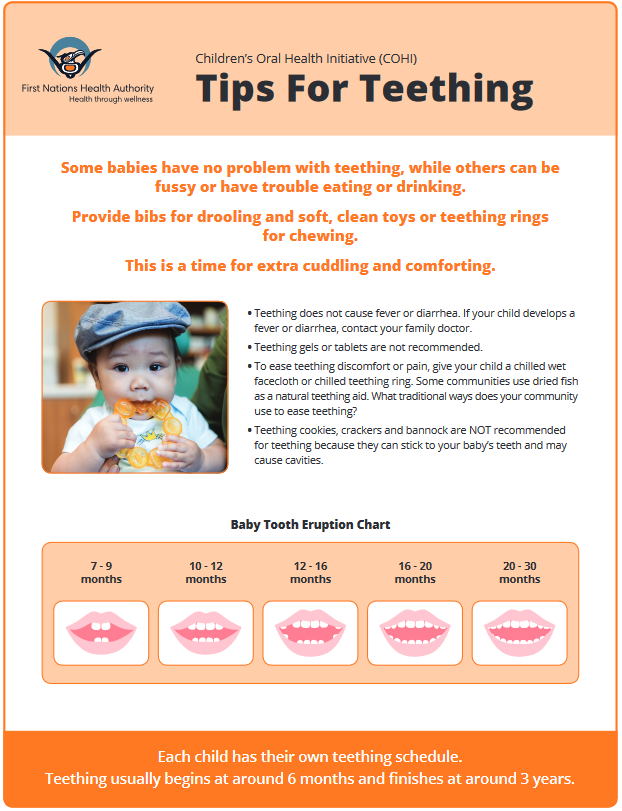

Among the population of Children in Canada, some come from backgrounds that are more vulnerable to oral health problems. Continuing my research on children's oral health, I branched out to the First Nations population. In 2011 the First Nations Oral Health Survey (2009-2010) reported that approximately 86% of First Nations preschool children aged 3–5 years had experienced dental caries. Lack of oral health knowledge among expectant and new mothers, as well as poor nutritional habits in pregnancy that are passed onto the child are primary concerns. The Children's Oral Health Initiative was launched in 2004 to help educate expectant and new mothers about oral health. I was impressed by the educational posters the COHI created and intend to utilize them in the future; they provide clear and effective messages that can reach a broad audience (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.).

Future Health

Finally, as my journey in the MHST 601 course came to a close, I searched for information on the future children's dental care. Children can be challenging to treat in the dental office, primarily due to fear. Intervention with pharmacotherapy is often necessary for restorative treatment, however, Goettems et al (2019) discussed potential alternatives to pharmacotherapy, one of which was the use of virtual reality (VR) glasses. Adult patients have successfully used VR to alleviate dental fear and I look forward to learning about VR use for dental procedures on children.

Conclusion

The MHST 601 course provided me with a valuable learning experience into the realm of oral health and overall health. I have strengthened my research and analysis skills, developed a comprehensive collection of curated content and have a better understanding of the state of children's oral health in Canada. I look forward to continuing to learn and explore my area of interest during my academic and professional career.

References:

Bircher, J. (2005). Towards a Dynamic Definition of Health and Disease. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 8(3), 335-341. Retrieved May 30, 2019 from

Canadian Dental Association. (n.d.). Your Child's First Visit. Retrieved June 22, 2019, from http://www.cda-adc.ca/en/oral_health/cfyt/dental_care_children/first_visit.asp

College of Dental Hygienists of Nova Scotia. (2014). Dental Hygienists Prevent More to Treat Less. Retrieved May 15 2019 from www.cdhns.ca/images/Prevent More to Treat Less OCTOBER 2 FINAL.pdf

First Nations Information Governance Centre. (2011). Report on the Findings of the First Nations Oral Health Survey (FNOHS) 2009-2010 National Report. Retrieved July 5, 2019 from https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/docs/fn_oral_health_survey_national_report_2010.pdf

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). Children's Oral Health Initiative //. Retrieved July 5, 2019, from http://www.fnha.ca/what-we-do/maternal-child-and-family-health/childrens-oral-health-initiative

Government of Canada. (2019). Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequalities. Retrieved June 05, 2019, from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html

Huber, M. (2011). Health: How should we define it? BMJ: British Medical Journal, 343(7817), 235-237. Retrieved from http://0-www.jstor.org.aupac.lib.athabascau.ca/stable/23051314

Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness. (2004). Standards for the Nova Scotia Fluoride Mouthrinse Program. Retrieved June 28, 2019 from https://novascotia.ca/dhw/healthy-development/documents/Standards-for-the-Nova-Scotia-Fluoride-Mouthrinse-Program.pdf

Nova Scotia. Department of Health and Wellness. (2014). Nova Scotia public health: Healthy development protocol. Halifax, N.S.: Dept. of Health and Wellness.

Nova Scotia Department of Health & Wellness. (2019, Jan) Dental Facts: Children’s Oral Health Program. Retrieved May 14 2019 from https://novascotia.ca/dhw/healthy-development/documents/DentalFactsMSIChildren_En.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2017). The State of Community Water Fluoridation across Canada. Retrieved June 13, 2019, from http://www.publichealth.gc.ca

Rimer, B. K., & Glanz, K. (2005). Theory at a glance: A guide for health promotion practice. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute.

University of Toronto. (2012, April). Water Fluoridation Questions and Answers. Retrieved June 15, 2019 from http://www.caphd.ca/sites/default/files/WaterFluoridationQA.pdf

Comments